An American Woman Mining Gems in Pakistan

For those feeling disappointed or questioning the future role of women, I hope this morning’s story brings a sense of optimism about what is still—and always will be—possible. Now with audio!

I almost didn’t publish the Global Women’s Disruptors article today because it seemed counterintuitive to the prevailing narrative, given that Harris lost the election. However, it made me reflect: Women continue to be highly disruptive in a positive sense around the world, and it’s crucial to acknowledge that.

For those feeling disappointed or questioning the future role of women, I hope this morning’s story brings a sense of optimism about what is still—and always will be—possible.

After a panel discussion on voting with influential media and entrepreneurial women in DC, Nida Jamal maneuvered through the crowd, determined to meet the speakers. She unapologetically asked for their LinkedIn or contact information, a move many in the crowd longed to make but were too shy to attempt.

It’s this boldness that allowed Jamal, a woman who wears her colorful hijab loosely, to start a business mining gemstones in the rugged mountain regions of Pakistan.

Doing business in Pakistan isn’t for the faint-hearted. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business index, Pakistan ranks 108th out of 190 countries due to the structural and logistical challenges of entrepreneurship. But Jamal, an expert networker turned philanthropist and businesswoman, has sought to build a sustainable industry in the most rural parts of the country—not for herself, but for the women in the mountains.

A Creative Business Opportunity With Purpose

Jamal is the wife of a surgeon with the luxury bags to prove it. So for her, the mission isn’t profit so much as it is sustainability: to empower women in Pakistan’s remote mountain regions by giving them a way to sustain themselves through the art of gemstone mining and jewelry-making.

In the past, many of these women had been part of aid programs that helped them develop their skills in jewelry-making and stone-cutting. But the problem, as Jamal explains, was that the funding was often short-term, and the women were left with no way to continue.

“They would get funding to learn how to make the jewelry, but once the money ran out, that was it. They had all these skills but nothing to do with them,” she says. “It was so frustrating to see all this potential go to waste.”

So, for her, business was a way to give them something with dignity.

“I didn’t go into this thinking I’d be a businesswoman,” she says with a laugh. “I went into the region, saw these women who had all these skills but no resources. I knew I had to help.”

But it’s not all altruism. Jamal gets something deeper than money out of the deal, something at the top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. She gets self- actualization, to experience purpose.

“I don’t want to be known as just the surgeon’s wife or the mother of five children,” she explains. “I want to be known for this. I want to leave a legacy, something that I built, that has a lasting impact.”

Laying the Foundation For an Export Business

Jamal was on vacation with her husband and five children when she first ventured into the mountains of Pakistan.

“I met these women who were making beautiful jewelry. I bought a few pieces, not thinking much of it,” she recalls. “The first time, I was just figuring out what was there—what gemstones, what skills these women had.”

On her next trip, she returned with a mission. The trip was carefully planned, and it wasn’t just about sourcing gemstones. She was building relationships and understanding the environment these women lived and worked in.

To navigate the bureaucratic and tribal complexities of working in Pakistan’s remote mining regions, Jamal knew she had to secure the proper permits and clearances. This wasn’t a straightforward process—she relied on a web of connections, calling on friends of friends and leveraging her personal network to get introduced to the right people.

"I had to meet with the heads of regions, tribal leaders, and even princesses," Jamal explains.

Each introduction was critical in gaining the permissions she needed to enter the mines and establish her business. When meeting these powerful figures, she made sure her pitch was clear: she wasn’t seeking personal gain, but rather to help the women of the region create sustainable livelihoods.

"I don’t need your money," she told them. "But what I do need is for you not to bother me. And I need clearances because I want to go into the mines."

Her mission to empower women, combined with her strong connections, opened doors that would have remained firmly closed in a gem industry riddled with smuggling. By leading with her genuine intent to improve the lives of local women, she was able to navigate spaces that would typically be off-limits to outsiders, especially women.

Overcoming Cultural Barriers to Get the Job Done

The mines are typically male spaces, and the idea of a woman entering them, let alone leading a business there, is foreign and often met with suspicion. But Jamal says the reality isn’t as the Western media portrays it. Sure, it’s unusual for her to be sitting alone with men in the mountains, but she’s done the work of establishing trust.

“These men are some of the most respectful people I’ve met,” she explains, emphasizing how they came to view her as an ally.

Now, she ventures into the mines with the men, feeling safe as she sits, talks, and checks gem sources with them.

But beyond gender, Jamal also faced challenges as an outsider to the local tribal communities. Though she is Pakistani-American, she’s not from their tribe, doesn’t speak their language, and differs in appearance and mannerisms. In tribal cultures, kinship ties and community connections are essential, so being an outsider adds layers of distrust.

Jamal recalls how her presence initially attracted the attention of local intelligence agencies, suspicious of her motives due to the high rates of gemstone smuggling. Yet, through persistence and respect, she has broken down these barriers.

“They said, ‘Look, you're here to help our women,’” Jamal recalls. “You tell us what you need from us. We don’t want your charity, we don’t want your money. All we want is for you to help our women get trained and empowered. And I was like, okay, I can do that.”

Tribal leaders, many of whom have deep mistrust of outsiders, especially Westerners, were reassured by her commitment to empowering the women of their communities rather than exploiting them.

The Current Business Model and Why It’s Different

Jamal’s business model is both simple and unique. She works directly with local artisans and miners, cutting out the middlemen who often exploit the system and sell the products in the United States.

She’s made a point to know all her team members personally and makes herself accessible through a WhatsApp group where about 150 women from various regions communicate with her and each other.

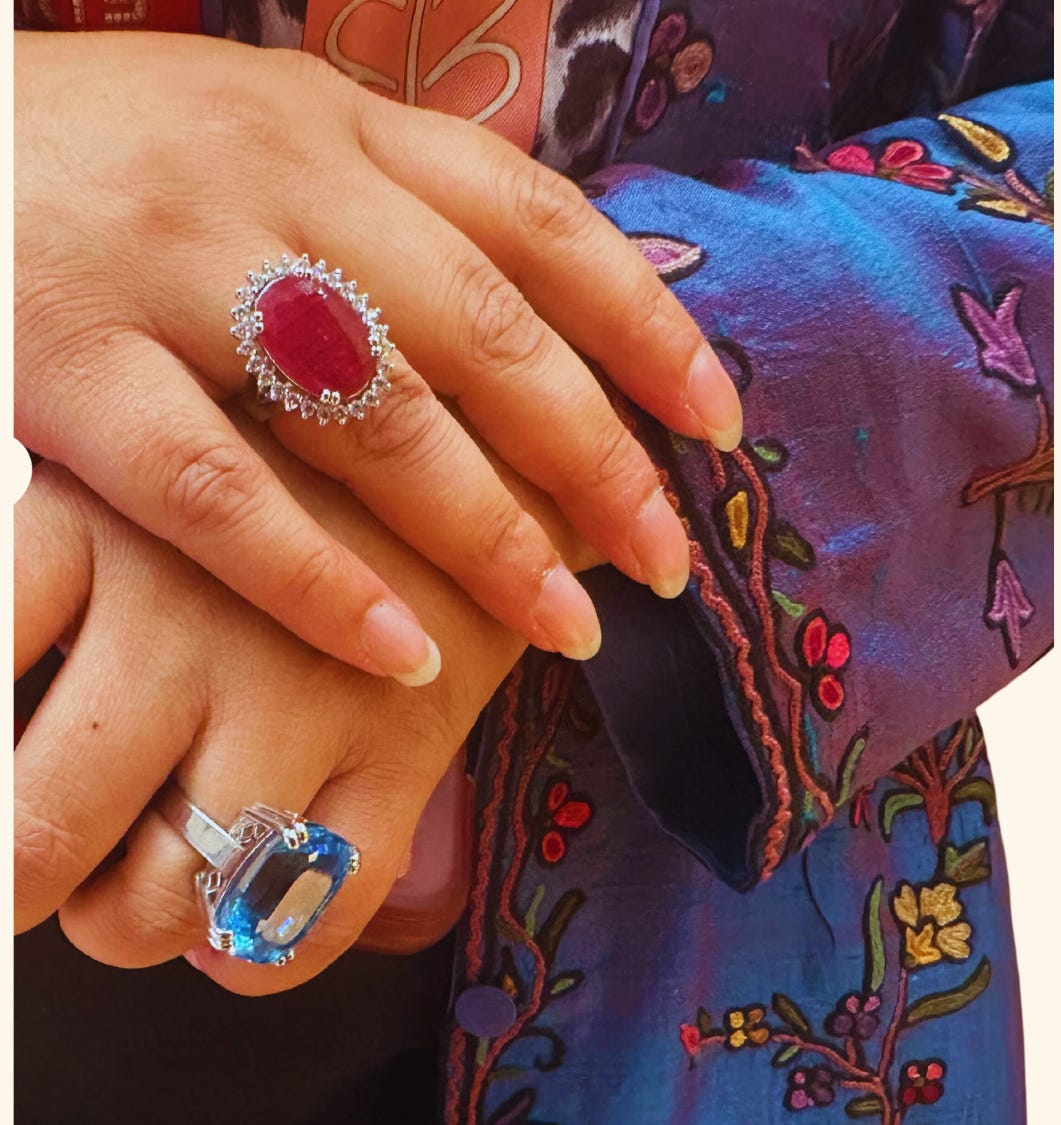

“I don’t mass-produce anything,” she says, noting she sells out every time she brings her products to the United States. “I might have 300 products, and once they’re gone, they’re gone. People actually wait for us to release more.”

Her model contrasts starkly with the traditional gemstone and jewelry industries, which often rely on mass production and unclear sourcing practices.

“I don’t work with diamonds because I can’t trace them back to their source,” she explains, adding that diamonds are also not available in Pakistan. “Our gemstones are hand-extracted from mines I’ve visited personally. I know the people working there, and I know the conditions.”

While this design limits the scalability of her business, Jamal is fine with that. She has deliberately chosen to keep her production small and exclusive.

“Our pieces are handmade, and it can take months to create them,” she says. “That’s what makes our brand different. People know they’re getting something unique.”

At the end of the day, Jamal believes that running her business this way allows her to create the sustainable change she wants.

"I pay the women four times more than they would get elsewhere," she shares. “One woman told me, ‘I was able to take my son to the hospital because of the opportunity you gave me.’ Another woman said, ‘I can now send my kids to school.’ That’s why I do this.”

The State of ArHaz 10 Months In

Just 10 months into her business, Jamal has already sold out multiple collections.

“Every time I come back to the U.S. with more jewelry, it’s gone before I know it,” she says.

With her Pakistani roots and her surgeon-spouse’s social circle, she is the perfect bridge between product and market.

Her brand, ArHaz, named after her daughter Zahra but spelled backward, is quickly gaining recognition.

“I wanted a name that was meaningful,” she explains. “I did my research, and in pre-Persian, ‘ArHaz’ has roots in creativity and nobility. That felt right.”

Jamal has also recently joined international women empowerment groups through her work and is now a fellow with Vital Voices. Despite early success, she knows there’s more work ahead.

“We’re still small, but we’re growing. My husband says just break even,” she jokes, noting the thousands of dollars in personal capital her family has invested in the venture. “I’m doing it in a way that stays true to our values.”

What She Still Needs to Make It All Work

To make her business truly sustainable, Jamal needs more than just demand—she needs infrastructure.

Recalling her trips to the mountains, she describes being stuck for eight hours due to a rockslide. Some of the regions she travels to have unstable electricity and almost no cell service.

“Right now, I don’t have a team of 20 people running the business,” she says, thoughts of the pieces she needs to assemble running through her mind. She pauses, then asks if I know a good product photographer. “It’s just me and a few close contacts. I’m working on building out a website, getting my export license, and growing the business.”

One of her long-term goals is to partner with luxury retailers to showcase her higher-end pieces.

“Our quality is on par with international brands,” she says proudly, noting that the same women who cut stones for luxury French brands are cutting hers.

Even through the challenges, Jamal has found peace. In the mountains, no one cares about her luxury bags, and sometimes she basks in the calm that comes from losing cell service.

What Jamal has done is almost impossible to replicate, but the lesson is clear: good business can come from doing good, and your network is priceless.

You are now more cultured because you now know opportunities for women in countries like Pakistan are far more complex and nuanced than what traditional Western media often portrays. These stories challenge stereotypes and open new paths for empowerment.

Ready to become a paying subscriber?

Next Steps:

If you like what you see, click subscribe.